ARE TODAY’S PROBLEMS CAUSING MORE CHRISTIANS TO LOSE FAITH AND COMMIT SUICIDE, OR IS THEIR FAITH AND HOPE GREATER THAN NON-BELIEVERS?

Read first the article that came out today and then read the article following, which is the results of a survey taken about one year ago, concerning this subject matter. The true question is: Are suicide rates among Christians going up, or are they going down? Examine the information then you decide.

When you see the survey that follows this article, and you come to the part that shows you the percentage of suicides among various countries, it is interesting to note that among the highest rate of suicides among advanced and progressive countries, Japan, Russia, Canada and the United States are relatively high. For America, a country supposedly founded as a Christian nation, its suicide rate is exceedingly high. Why?

With the exception of Kuwait (which has the lowest suicide rate, and is probably (per capita) the richest country in the world (all that oil helps), the lowest suicide rates are found predominately in poor Latino, Hispanic, Spanish-speaking nations, like Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Paragua and the Dominican Republic . Surprisingly, Britain and Ireland are also very low, much lower than the U.S. Why is that? You tell me!

In His Peace,

Joe Ortiz

Rising Unemployment Rate Forecasts Increased Suicide Among Protestant Christians

GREENVILLE, SC, Aug. 11, 2009 /Christian Newswire/

As unemployment rates rise around the United States, experts predict a corresponding rise in the suicide rate. Recognizing that the Christian community is not exempt from this trend, South Carolina-based Prasso Ministries is offering tools to help people build a faith that sustains and grows in times of crisis.

According to Dr. Harvey Brenner at John Hopkins University, for every one percent increase in the unemployment rate, an additional 1,200 people can be expected to commit suicide.

And the Christian community is not exempt. ReligiousTolerance.org reports that among faith groups in the United States, Protestants--despite their stand against suicide--have the highest suicide rate.

"That's tragic and yet understandable," confirms Laura Baker, executive director of Prasso Ministries. "Many people who have been in church all their lives still have their faith knocked out from under them due to job or financial loss brought on by the recession."

July 3, 2008

In More Religious Countries, Lower Suicide Rates

Lower suicide rates not a matter of national income

by Brett Pelham and Zsolt Nyiri

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Gallup Polls from 2005 and 2006 show that countries that are more religious tend to have lower suicide rates.

The 2005 and 2006 Gallup Polls asked respondents whether religion was an important part of their daily lives, if they had attended a place of worship in the week prior to polling, and whether they had confidence in religious organizations in their countries. The Gallup Religiosity Index reflects the percentage of positive responses to these three items. A nation's index score speaks to that nation's overall level of religiosity. Comparing the Religiosity Index scores of different countries with suicide statistics published in 2007 by the World Health Organization reveals a clear pattern: Countries that are more religious tend to have lower suicide rates.

For example whereas the Philippines has one of the world's highest religiosity scores (79), Japan has one of the world's lowest scores (29). Suicide rates in the Philippines are almost 12 times lower than rates in Japan. Paraguayans, who are much more religious than Uruguayans are, also have suicide rates about five times lower than in Uruguay. The United States falls near the middle of the international pack in religiosity, at 61. The United States also falls near the middle of the international pack in suicide rates, having the 32nd highest suicide rate out of 67 countries.

Because recent suicide data were unavailable for many countries, it was not possible to extend this analysis to include more than 67 countries. Despite this limitation, the suicide-religiosity association does not seem to be restricted to any specific set of countries. For example, for the 12 former Soviet Union countries that data were available for, the suicide-religiosity association was even stronger than for the sample as a whole. Most notably, Armenia, Georgia, and Tajikistan have relatively high religiosity scores, especially in comparison with other former Soviet Union countries. All three countries also have low suicide rates. Tajikistan is also notable as one of the few countries in the sample with a substantial Muslim population (Kazakhstan is another). Tajikistan's Religiosity Index score is higher than Kazakhstan's, and suicide rates in Tajikistan are lower than Kazakhstan's rates.

Does religiosity per se truly affect suicide rates? Countries that differ in religiosity often differ in other ways. For example, these same data showed that less religious countries are usually wealthier (e.g., have a higher GDP per capita) than more religious countries. Further, these data showed that suicide rates are also slightly higher in wealthier countries. However, the relation between GDP and suicide is not nearly as strong as the relation between religiosity and suicide. Thus, national wealth cannot explain the connection between religiosity and suicide. Another concern is that countries that are more religious might tend to underreport suicides -- because of subpar medical documentation, or the added social stigma suicide carries in countries that are more religious. However, an analysis focusing only on wealthy countries, where documentation of suicide is likely to be excellent, still reveals a robust association between religiosity and national suicide rates.

A final hypothesis is that greater social capital (collective commitment to social well-being) in more religious countries could be responsible for the lower suicide rates observed in these countries. However, if greater social capital explained why higher religiosity is associated with less suicide, one would probably expect to see lower homicide rates in more religious countries. In these data, however, homicide rates were actually somewhat higher in countries that are more religious.

Do these country-level findings translate into the behavior of individual people? Large-scale studies of individual respondents suggest so. In 2002, statistician Sterling Hilton and colleagues showed that among young men who were actively involved in the Mormon church, suicide rates were three to five times lower than those of either non-members or less active church members. Moreover, in a review of 42 studies of religiosity and mortality, Michael McCullough and associates showed that, compared with less religious people, highly religious people are slightly less prone to mortality from several specific causes, including suicide. Finally, recent respondent level data from other Gallup Polls show that religious people are much less likely than the general public to believe that suicide is "morally acceptable." Perhaps the most extreme example of this comes from France, where 40% of the general population but only 4% of Muslims living in Paris consider suicide morally acceptable.

It is thus possible that religion serves as an antidote to the lack of purpose that can make a desperate act such as suicide seem appealing. Believing in something bigger than oneself may allow some people to hold onto life in a world where people without such a belief sometimes give up all hope. Another possibility is that some religious people may believe that committing suicide jeopardizes their security in an afterlife. Alternately, the human connections that people typically forge in religious groups may serve as a buffer against suicide. Whatever the reason for the religion-suicide link, these results suggest that leaders who wish to understand the well-being of a country must look beyond traditional economic indicators. When it comes to well-being, spiritual concerns may be at least as important as economic ones.

Survey Methods

Results are based on telephone and face-to-face interviews conducted in 2006 with approximately 1,000 adults per country. For all of the countries reported here, confidence intervals for mean Religiosity Index scores were within + 3 percentage points from the national percentages shown here. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

The bottom line is, God will never burden you with more than you can handle, and is within shouting distance to hear your please for help!

In His Peace,

Joe Ortiz

8/11/09

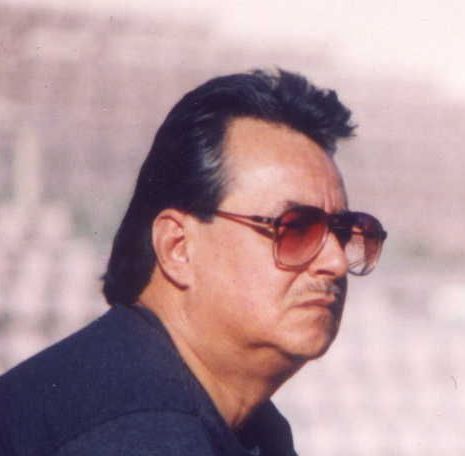

Joe Ortiz is the author of "The End Times Passover" and "Why Christians Will Suffer Great Tribulation," (Author House), two books that challenge Christian Zionism, the Pre-Tribulation Rapture, and all Left Behind mythology. The former newsman, newspaper columnist and talk show host, has the distinction of being the first Mexican American to host a program on an English-Language, commercial radio station (1971, at KABC-AM, Los Angeles).

1 comment:

Our son, Joshua died by suicide (or penacide--see www.joshuaalive.org)in 2007. He was 24, raised a Christian,and tried to live a life of obedience to God. He was also sexually abused as a child--incest.

Suicide and sexual abuse are two topics that within Christianity are not often, if ever, spoken of. Recent studies show more and more of a link between childhood sexual abuse and suicide later in life.

Societies like ours who claim a corner on the good life (i.e. the American Dream), and like to think they are God's favorite, are not likely to expose the dark side of worshipping ourselves, our achievements, and way of life.

I tend to think that official statistics on suicide and sexual abuse, while useful in some ways, are much higher than reported. Unfortunately, shame and denial still carry the day.

Suicide/penacide is not helpful. It traumatizes those left behind. Yet I do not believe that condemning or stigmatizing those who die bereft of comfort on this earth is healthy or truthful either. It certainly doesn't help their families. Carefully guided open discussion and what I call "death education" is what is needed. And by this I mean that there should be no subject that cannot be brought into the open and talked about. Deathly silence is not the answer; that which is brought into the light becomes light.

Post a Comment